Ehsan Sheikholharam, Kennesaw State University

Keywords: atheist spirituality, laïcité, pluralist ethics, post-Christian Europe

It’s not surprising to hear that someone identifies as Jewish, while not believing in a transcendental God. Likewise, it’s not unlikely to hear that some Muslims don’t observe daily prayers or believe in the Day of Judgement. The categories “cultural Muslim” or “secular Jew” are well established and widely used. But what about “athée fidèle,” or faithful atheist? What are the implications of declaring oneself atheist, while also remaining faithful to Christianity as a tradition?

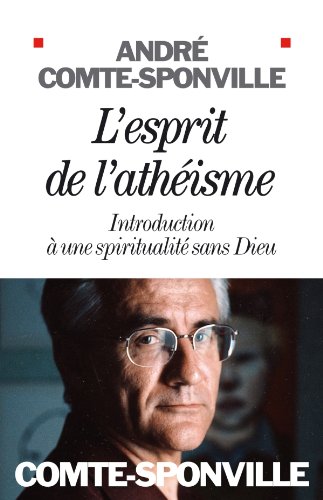

In his 2006 publication, L’Esprit de l’athéisme: Introduction à une spiritualité sans Dieu, French philosopher André Comte-Sponville presents his case for spirituality without God. One does not need to throw out the baby of culture with the bathwater of organized religion. For Comte-Sponville, Christianity is not simply a religion among the rest. It represents a vast philosophical, literary, and social tradition that can still offer valuable intellectual and moral resources for life in the 21st century.

Unlike the populist claims about the decadence of the Judeo-Christian civilization by thinkers such as Michel Onfray, or the xenophobic framings of Islam as the civilizational Other of Christianity by Marcel Gauchet, Comte-Sponville’s The Spirit of Atheism takes on an optimistic and positive tone. It draws on diverse cultural, spiritual, and intellectual traditions of Europe to build a new re-enchanted collectivity.

André Comte-Sponville’s advocacy for reframing Christianity as a tradition worth defending emerged out of his worries about two tendencies in secularized France. First, the disoriented youth—who no longer believe in a religion—often face difficulties in finding a moral compass. Second, the historical process of secularization (laïcisation) did not eliminate religion. Instead, it created disembodied religiosity: beliefs without collective rituals or public presence. This forcing out of religion from the public sphere contributed to the rise of new forms of extremism and religious fundamentalism.

Even before the post-colonial growth of Islam in Europe, the continent’s intellectual and cultural traditions were diverse, and to a certain degree, contradictory. From Greek paganism to Israelite monotheism, from the Talmudic Law to Epicurean hedonism, and from the Inquisitions to the Enlightenment, European heritage encompasses elements that are not oriented towards a singular nexus. Within this mixed heritage however, some commentators have traced lines of continuity — as reflected in the hyphenated term “Greco-Judeo-Christian.”

Today however, many have suggested that this civilizational lineage is in a state of decline. Statistics point to the waning of church attendance on the one hand, and the emergence of new forms of religiosity, on the other. Many of the latter exhibit tendencies towards obscurantism and fanaticism. To ‘save’ the intellectual, cultural, and spiritual heritages of Europe, André Comte-Sponville embraces Christianity as a repository of ethical values worth preserving. Unlike the paranoid and xenophobic outcries of far-right voices in France demanding a return to the “Judeo-Christian roots,” Comte-Sponville doesn’t subscribe to the essentialization of the tradition. He keeps the genealogy open and invites a pluralist reading of Europe’s history. Europe is inevitably becoming more diverse, ethnically and culturally. The book is a remedy for his compatriots who are troubled by the unraveling of their national, ethnic, and cultural identities. It offers those anxious about the presence of other cultural expressions, especially immigrant identities, to feel grounded in Europe’s larger civilizational substance.

By setting aside confessional religions as well as a religiosity embedded in the belief in a transcendental divinity, Comte-Sponville’s “Godless” spirituality presents a vision of reenchanted collectivity that is more open, tolerant, and resourceful. What is important here, is that his version of atheist spirituality doesn’t discard aspects of culture only because they carry vestiges of religion. He regards Christianity as the repository of diverse moral values and civilizational resources of the West, especially Europe. Yet one does not need to believe in Christian God to engage with cultural and spiritual resources associated with Christianity.

Proponents of the “secularization thesis” professed that with Europe’s progress towards rationalization, religious authority (and religions more broadly) would decline from the public, political life. It is naïve, however, to declare their prophecy readily bankrupt. While certain types of religious commitments are in decline, other forms are on the rise—especially when one compares the decline in church attendance with accounts of religious violence. Furthermore, with the rise of anxieties over ethnic identities, religious sentiments lend themselves to forms of communitarianism. On the one extreme, there are metonymies of white, conservative, ultra-nationalist, neoliberal, anti-immigrant politics; on the other, Salafist, Islamist, and separationist outcries. Comte-Sponville bemoans that new religious phenomena lean toward obscurantism, dogmatism, and fundamentalism. To save Europe and its Enlightenment heritage from both of these tendencies, one does not need to fight religion as such. To the contrary, the Judeo-Christian tradition, according to him, can serve as a repository of cultural and civilizational resources that can foster more open forms of shared values and collective identities. Comte-Sponville underlines values such as compassion, humility, and fraternity without falling into traps of identity politics. On a more practical level, he advocates for teaching religion in public schools solely as a historical and social phenomenon. Enshrined in the principle of laïcité and freedom of conscience, this secular education will help to restore a sense of collective heritage beyond race, ethnicity, or any other exclusionary categories.

Religio, religare or religio, relegere?

Comte-Sponville draws on different etymologies of religion to make a case for his atheist spirituality. In the first formulation, he traces religio to religare and the French relier. Religion in this sense operates as a social bond and offers common values necessary for social cohesion. Secondly, he examines religio in connection to the Latin relegere, connoting the act of reverent and contemplative reading. In this latter sense, religion is akin to the love of a Logos. Using these definitions, then, Comte-Sponville’s privileges the joy of life over religion of fear and persecution, communion over sectarianism, loyalty to ethical values over blind faith, and love over otherworldly hopes and despair.

To popularize his pluralist ethics, Comte-Sponville evokes binary choices that are difficult to disagree with. Across cultures, he suggests, courage is valued over cowardice, sincerity over lies, and kindness over cruelty. His atheist spirituality, therefore, is a patchwork of “values” woven from diverse religious cultures.

But should the universal horizon of understanding be built upon religious values? Can foundational values capable of fostering social cohesion be made up of “secular” elements such as equality between the sexes, the chance to participate in democracy, or the right to secular education? Such questions are – at their root – political questions. Which history should be included in public schools: the history of Christianity or civilizational exchanges across religions/cultures? In short, is European democracy a product of the Enlightenment’s critique of religion or a historicist development of Christianity itself?

Closing Thoughts

L’Esprit de l’athéisme inspires readers to formulate new questions surrounding the role of religion in public life. Can Europe rely on something other than religion to create a shared horizon of history and a foundation for cultivating social cohesion? Isn’t Europe’s legacy in music, literature, philosophy, and architecture powerful enough to serve such a purpose?

On a material level, Comte-Sponville doesn’t assign Christianity the task of building social solidarity. He doesn’t trust charity—whether individual acts of generosity or organized religious giving—as a means of ensuring everyone’s right to a dignified life in a capitalist society structured around individual and egoist interests. Instead, he urges his compatriots to defend collective solidarity as expressed in the state’s social programs. It is primarily in building a shared symbolic horizon that he promotes critical engagements with Judeo-Christian tradition.

But has not the time come to find new horizons? For many, the call has long been overdue. Alain Badiou, for example, reformulates the concept of neighborhood to envision new forms of collectivity organized on porous boundaries and shared experiences. Bruno Latour, Michel Serres, and Philip Descola, for their part, advocate for new modes of collectivity and social contracts that recognize the Earth and “all the Living” as subjects of right and collective decisions.

Contrary to self-serving oppositional framings of Islam versus the West, Comte-Sponville’s philosophy promotes trans-civilizational affinities. To highlight shared horizons, he elaborates how Spinoza’s notion of immanence resonates with key elements of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism. In formulating a “wisdom for our times,” Comte-Sponville selectively connects these dots in surprising but delightful fashion. Andre Comte-Sponville’s philosophical project is complex, nuanced, and at times ambivalent. While this brief reflection cannot capture the depth and breadth of his thinking, I hope that this piece sparks your interest in learning more about this work.

Ehsan Sheikholharam has a multidisciplinary background in architecture, religious studies, and philosophy. He holds a Ph.D. in Religious Studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a terminal degree in Architecture from the University of Miami. He has also served as the Coordinator of Religion and Public Life fellowship at the Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke University. Building on his diverse scholarly and cultural identity, Ehsan’s work cuts through key questions in the Humanities and design disciplines, including representations of minority identities in public space and critical cultural productions in the Global South. He is currently an Assistant Professor of Architecture at KSU.