Dani Gaudette, The University of Tampa

Keywords: soul belief, afterlife, Norway, Finland, nonreligion, secularism

Developing countries are experiencing secularization, leading to a noticeable decline in religious beliefs. Since this change is still underway, its long-term impacts on people’s beliefs around the world are unclear. Without religious traditions offering guidance, we may ask: What do the nonreligious value? What do they believe? How do they make sense of their lives? During my junior year at The University of Tampa I began working with Dr. Ryan Cragun, who introduced me to the Nonreligion in a Complex Future (NCF) Project. This project aims to investigate the above questions and more. Together we began exploring data from the Cultural and Social Values Survey administered by the NCF project, in search of some insight on the perspectives and beliefs of the nonreligious.

In 2023, the Pew Research Center released a report on religious ‘nones’ – those without a religious affiliation – in the United States, finding that approximately 67% believed in a soul, while only 36% believed in an afterlife. We found this discrepancy intriguing, as it seems counterintuitive at first glance. If someone believes in a soul, wouldn’t it make sense for them to also believe in a life after death? We began by questioning what causes this discrepancy. Could it be that a significant proportion of people hold inconsistent beliefs? Or could something else be at play, like respondents interpreting survey questions differently from researchers?

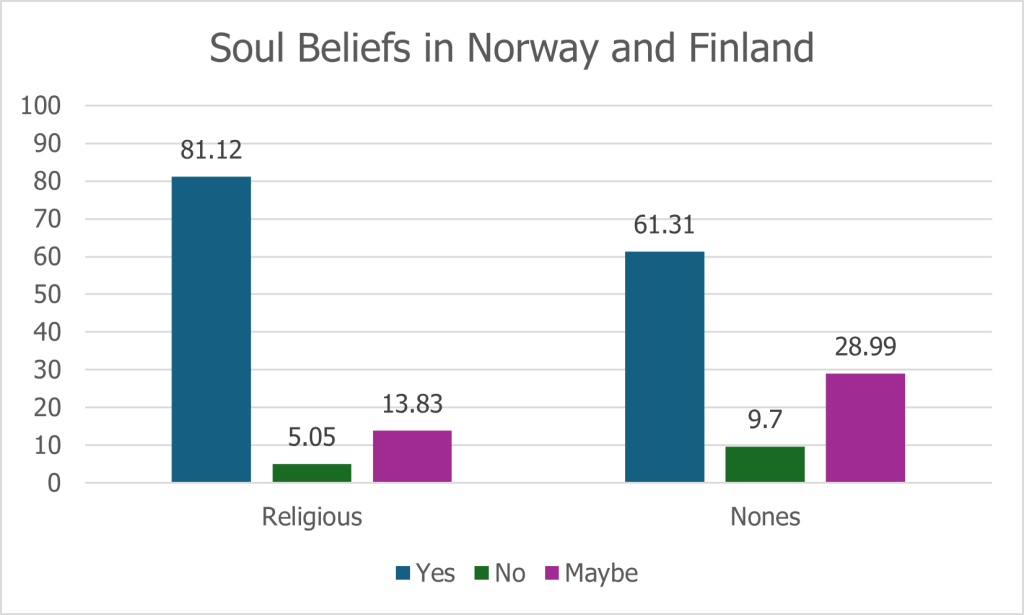

To explore this further, we analyzed whether our own survey data reflected a similar trend as the Pew report. Of the eight countries surveyed, we began with Norway and Finland. Just as the Pew report observed in the US, we found a gap of about 30% between ‘nones’ who believe in a soul and those who believe in an afterlife.

A quick Google search for the definition of “soul” gives the following: “the spiritual or immaterial part of a human being or animal, regarded as immortal.” This was the definition that I held at the start of this project. I found that many others I discussed the topic with shared the same understanding. Similarly, if you search for a definition of “life after death” you’ll get a similar answered with some aspect of a person continues to exist even after their physical body dies.

Given these definitions, it is surprising that many people report believing in a soul but not in life after death. After all, the two concepts seem so deeply related. This disconnect is exactly why we found these results so intriguing.

The figure above attempts to illustrate this peculiarity. Not only do a significant proportion of ‘nones’ believe in a soul; there is a notable proportion of the religious who do not believe in a soul. Together, these observations suggest that the soul as a natural concept – in contrast to a supernatural concept – is not exclusive to the religious. Furthermore, this belief is not universally held among the religious.

Much of the literature on the soul is rooted in theological or philosophical perspectives. There are few sociological studies to base our work on. Regardless, some relevant research exists. Richert and Harris, for example, investigated the concept of dualism – the belief that the physical and mental properties of the body are distinct.[i] Martyn has also conducted several studies on how people (specifically medical students) conceptualize the soul, and what it means for them.[ii]

A few key themes throughout the literature are worth noting: there is no single, universal soul concept, and the soul is often closely connected to notions of identity. In W. E. B. Du Bois’s famed work, The Souls of Black Folk, soul is referenced in a distinctly different manner.[iii] Here, it captures the ideas of the shared experiences, culture and history of the Black community, in contrast to the more personal interpretations we focus on in our research.

To explore what factors influence belief in a soul, our study uses statistical analysis to uncover patterns across different demographics. We are investigating religious factors such as religiosity and religious affiliation, as well as basic demographics like gender, education, and age. Based on existing research on beliefs and related concepts, we anticipate trends in soul beliefs associated with these factors. By identifying those who hold belief in a soul, we can lay the groundwork for qualitative analysis to look deeper into how people conceptualize the soul. As secularization continues, understanding the different ways people think about concepts like the soul becomes important in discovering how they experience the world around them. Our work not only addresses the gap we observed in the sociological literature, but also opens up opportunity for deeper discussions about ways that we find meaning. By exploring these beliefs, we may uncover unexpected commonalities that connect the religious and nonreligious in unexpected ways.

Dani Gaudette is a senior undergraduate student at The University of Tampa studying Applied Sociology and Biochemistry. She began working with Dr. Ryan Cragun on this research in January 2024 as a part of the Nonreligion in a Complex Future project. Since the start of her research, Dani has presented this work on various occasions including the ASR Annual Meeting in Montreal this past summer. She hopes to continue this research through her senior year with the goal of publishing the results.

References

[i] Richert, Rebekah A., and Paul L. Harris. 2008. “Dualism Revisited: Body vs. Mind vs. Soul.” Journal of Cognition & Culture 8(1/2):99–115. doi: 10.1163/156770908X289224

[ii] Martyn, Helen, Anthony Barrett, and Helen D. Nicholson. 2013. “Medical Students’ Understanding of the Concept of a Soul.” Anatomical Sciences Education 6(6):410–14. doi: 10.1002/ase.1372.

[iii] Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt). 1996. The Souls of Black Folk. Project Gutenburg.